THE HISTORY OF BAKER PERKINS INTERNATIONAL LTD., LONDON

For a background to the growth of Baker Perkins’ export business, see Group Developments – In Summary - Exports. Both exports and overseas sales of the Baker Perkins group increased rapidly through the 60’s and in 1970 exports from the UK reached £9.1m and production from the group’s overseas factories £16.4m. On January 1st 1969, a new company Baker Perkins International Ltd., came into being and Baker Perkins (Exports) stopped trading after 18 years’ life and over £47m worth of sales. This move was part of the re-organisation of the group’s overseas activities into six regions.

In 1971, the responsibility for international sales was given to the operating divisions and Baker Perkins International Ltd moved back to Westwood Works, Peterborough. At the same time the Latin-American regional headquarters was moved to South America, the group central London office and the European regional headquarters remained at Stanhope Gate in central London, which also housed the European sales office of Baker Perkins Inc’s chemical machinery division.

|

|

The Group Central London Office remained in Stanhope Gate until a move in around 1978 to 32, St. James' Street. By 1980 it had moved to 53, Grosvenor Street, finally ending up at 177, Kensington High Street where it remained for around 5 years until closure following the merger with APV in 1987.

As a result of this re-organisation, Baker Perkins International Ltd formed two new UK companies – Baker Perkins Latin America Ltd., responsible for all the group’s activities in the Latin American region, except Mexico, and Baker Perkins AIME Ltd, to perform a similar task in the Africa, India and Middle East region. Both companies had their headquarters at Westwood Works, Peterborough.

By 1976, Sales outside the UK (£47.7m) accounted for 69% of total sales, of which £20.6m or 30% of total sales represented exports from the UK – a record. The results for 1980 showed further growth with sales outside the UK, including £37.8m of exports from the UK, reaching £76.6m.

Making it happen

It is worth here taking a look at the many tasks and responsibilities that made up the day-to-day life of the export business.

Export selling might be considered to be a very glamorous activity – flying round the world, staying in first-class hotels or, as an ex-patriate, living the good life in a sunny climate. This misconception is easily dispelled by reading the recollections of Baker Perkins salesmen recorded in the accounts of the developments of the group’s activities in the various geographical areas of the world, listed at the end of this section.

|

|

|

| Correspondents, translators and telex operators at Stanhope Gate | ||

The salesmen and agents were only the ‘front line’ of the activity. Supporting them were the ‘correspondents’, a group of people responsible for organisation, communication and information, Colin Nichols recalls:

“We came into the picture as soon as we heard through a representative, agent or customer that new equipment might be needed. Our job was to gather as much relevant information as possible.. We had to supply technical information, organise plant layouts when necessary, and generally act as linkmen between the customer, the Export company and the factories at Westwood and Bedewell”.

It was a job where accuracy was essential. The customer had to know the exact size, weight and specification of each part of machinery; and everything had to be listed in detail to comply with the necessary Government import licences. The supplying factory had to have details of the site where the equipment was to be erected – accurate building plans, height above sea level, electricity voltage, gas, water and other services and what form of transport was to be used. All of this information formed the basis of the final quotation to the customer and the order specification that would be worked to by the factory. It was, of course, imperative that full details of the products that it was intended to manufacture should be cleared before the contract could be signed. Financial arrangements had to be agreed – letters of credit obtained and certified, insurance and shipping details confirmed. Any inaccuracies or mistakes could prevent, or significantly delay, the equipment leaving the dockside. Leonard Bush, who was in charge of the shipping department at Stanhope Gate, recalled:

“Before anything left the country we had to be certain that all the documents were in order, which involved an enormous amount of liaison with commercial and financial departments. All kinds of documents had to be raised according to the country being exported to – requiring a detailed knowledge of the destination country’s import licensing and financial regulations. Arrangements had to be made with the government’s export credits department, which was a form of insurance against making a loss. They covered us if there was any damage or loss for political reasons, such as a revolution, or a country running short of foreign exchange.

This was the paperwork side that the shipping department had to be sure was in order. To give an example of how complicated it could be, two people spent a whole fortnight checking the documents for a plant going to Brazil. One mistake, and the customer could have been fined heavily.

On the practical side of booking space aboard ship, the forwarding agents, who contact the shipping companies direct, were usually warned six to eight weeks in advance. Even then, we might have been co-ordinating plant from all over the country, and from outside suppliers. It was not always straightforward to ensure that everything arrived at the docks on time – if you were shipping to South America, and you missed a ship by a day here, it might have been several days before it could have been despatched – and even several months if the import licence had expired”.

Once every detail was clear, the shipping department could begin to plan the transport details – from which port, in which vessel, on which date, in how many crates, etc, etc. This was in the mid-60’s when equipment was shipped in large wooden crates, loaded onto a lorry for the journey to the docks, loaded by crane onto the ship and then onto another lorry at the port of arrival.

Things were changing with the advent of the roll-on/roll-off system in which a trailer was loaded at the works, driven straight on to the ship, and dragged off by another tractor at the other end for transport to its destination. This system was used mainly for European destinations but soon, even this method was to be superseded by the introduction of containerisation. By 1967, shipping containers were being used to send Baker Perkins equipment across the world. Door-to-door shipment became a reality

The correspondents were not only concerned with processing orders.

Customers both present and future had to be kept informed of new equipment and/or process developments and a close watch was made on developments - consumer lifestyles, disposable income levels, technical and political changes – that might have an effect on the potential for future business or in the way in which business would be done in the area.

The job was made more difficult by the problems of communication. Replies to a letter could take two weeks or so but, in the days before e-mail, most of the company’s agents used telex.

A key task was to translate the letters that arrived every day from customers all over the world and the material received from other group companies that had to be translated and despatched to every corner of the globe. This work occupied the full time attention of a staff of 11 fully qualified translators – four translating to and from German, three working on both the French and Spanish languages and one on Portuguese. Margaret Cooper Bruce was in charge of the department.

Besides their normal duties, the translators were sometimes called upon to act as interpreters and accompany customers on factory visits. They also attended most of the exhibitions at which Baker Perkins was demonstrating equipment.

Five telex operators transmitted to and received several hundred messages each day from offices thousands of miles away. A pool of ten typists coped with the flood of letters despatched each day. Three shipping and invoice typists and eight private secretaries were also part of the team.

The final task was to agree who would be travelling out from the supplying company’s Outdoor department to supervise the erection and commissioning of the plant on site (See also The Outdoor Men).

Stanhope Gate was also heavily involved in the business of exhibiting the group’s products at the many trade exhibitions that took place around the world each year (see also Trade Exhibitions). The export company, working with the group company in the country where the exhibition was to be held and the group company(s) who were to supply the machinery to be exhibited, began planning for the event often a year ahead. The first decision to be made was which machines were to be exhibited. Which were to operate (be in production on the stand) and what materials were to be used.

The export company agreed with the Holding company’s Publicity department (see also The Holdings Building), the design and layout of the stand. After this, it was down to the works staff at the supply companies – Baker Perkins Ltd, Rose Forgrove Ltd, etc. – to fit the production of these machines into an already crowded schedule. If a new design machine was involved, time had to be allowed for any complications that might arise, but regardless of the type of machine, there was little or no latitude – the date for shipping in time for the exhibition had to be met. The services of supply company engineers to install the machines on the stand – and keep them running – was also part of the planning.

At a major exhibition such as Interpack at Dusseldorf, Germany, there could be as many as 687 exhibitors and over 150,000 visitors. The day-to-day running of the company’s stand was no easy task. Frau Rene Inbar of Forgrove GmbH was responsible for the running of the stand at Interpack 1966 and spent three months of continuous hard work immediately before the exhibition getting things ready. Frau Inbar recalled:

“In the stand office, I was surrounded by ringing telephones (three lines, almost continually engaged, and 16 extensions), a telex machine chattering with messages to and from England, constant queries and the clatter of typewriters. There were around 120 staff on the stand – representatives form the export company in London, Baker Perkins Holdings, Baker Perkins Ltd, Forgrove, Rose and Job Day – and the complete sales and engineering staff from Forgrove GmbH as well as office staff.

Enough samples have to be available for customers to examine at their leisure. We wrote to 120 clients asking for samples of products wrapped on our machines and virtually all responded. The stand featured the equivalent of a shop – where you could obtain examples of some of the most interesting packages from all over the world. As well as this the machines on the stand had to have material to wrap – at any one time you could see machines demonstrating the wrapping and packaging of beard, cakes, trays of fruit, sausages, cheese, exercise books, toilet rolls trays of meat and sweets”.

For engineers, representatives and sales staff it was very hard work. The stand could not be left – even for lunch – in case an important visitor arrived. Standing on your feet for nine hours with scarcely a break is no sinecure.

When the exhibition is over the work is by no means complete. Machines had to be dismantled and shipped back home and there was still that mountain of paperwork to customers and potential customers who had visited the stand to be processed.

Despite the hard work, exhibiting at these major trade exhibitions was vital to the company’s prosperity. It is worth considering the task faced by the employees of Joseph Baker & Sons Ltd who were successfully exhibiting complete working factories at exhibitions around the world in the 1880’s without the aid of instant communications, containerised transport and other modern aids – and winning Gold Medals into the bargain.

While uncovering something of the truth behind the myths of the export business, we might also take a look at the life of the export salesman to see if that, too, matches our preconceptions. David Leroy was deputy international sales manager of Rose Forgrove, Leeds in the 1980’s and he gave his view of a day in the life of an export salesman in an interview with “Contact” in March 1980:

The Preconception

Leaping from his bed our hero greets the new day. Washed, shaved and dressed, he enjoys a hearty breakfast, takes fond farewell of his wife and leaves home.

His lightweight, but unbreakable suitcase is stowed in the boot of the awaiting taxi and away he goes to the airport. Our hero, one of the indefatigable team of export salesmen that spearhead our country’s export efforts is off on a sales trip, bringing the skill and technology that our industry offers to peoples of far-off lands, who eagerly await his arrival (so that they can put their new-found wealth into his hands).

Charming Stewardess

Soon after being courteously led through the simple formalities, he is comfortably seated in the aeroplane reading with interest the inflight journal provided by the charming stewardess who throughout the flight would ensure that his every need is satisfied.

He partakes of a light lunch with an amusing Burgundy and after a café-cognac dozes gently until softly advised by the stewardess that they will soon begin descent. She offers him refreshing hot towels, “perhaps another cool drink sir?”

On arrival his passage through the formalities is speedy as he presents the dark blue bound UK passport that ensures for its holder respect and problem-free travel. His suitcase is one of the first to arrive on the modern baggage-handling carousel and he is whisked away by his waiting agent to his air-conditioned limousine, in which he will, in a few moments, arrive at his hotel.

Sumptuous Suite

The doorman, an old friend, greets him as does the senior desk clerk. He registers and ascends in the express elevator to his sumptuous suite in which his case is already being unpacked by the valet.

He and his agent seated on the balcony in the cool evening air above the bustling metropolis, and its myriad necklaces of twinkling lights, partake of an aperitif which has arrived within a minute of a telephone call to room service, delivered by a smiling waiter who, with the famous custom of hospitality and service for which his country is known, refuses the tip offered and indeed returns some seconds later with more ice.

Our hero now takes delivery of his neatly pressed suits, freshens up in his sumptuous bathroom suite and rejoins his agent in the elegant surroundings of the dining room, which is finished in the grand manner of La Belle Epoque. The gourmet specialities of haute cuisine and regal allure delight their palates, as they are served by the unobtrusive, but ever-present team of waiters whose skill and pride in their metiér is worthy of comment.

During dinner the agent presents the full, but not overtaxing, programme of business meetings that he has arranged which includes ample, but not wasteful time, to permit our hero to take in some of the famous tourist attractions that the city offers.

Fine cognac

Finally, after a fine cognac, and excellent cigar, our hero takes

leave of his companion who has arranged for a limousine to be at the hotel

entrance at 9.30am the following day. Our hero retires to his bed relaxed

and confident that the next morning will see him refreshed and ready for

action.

The Reality

Let us now look back and examine the day as it really can happen.

- The airline timetable probably is so arranged that our hero crawls

out of bed at 4am in the dark, cuts himself shaving, has no breakfast,

waits for the taxi which is 15 minutes late and shouts goodbye up the

stairs to his sleeping wife.

- At the airport he discovers that the travel agent has put the

wrong flight number on his ticket. Not to worry, this confusion causes

little delay as the plane is two hours late in taking off.

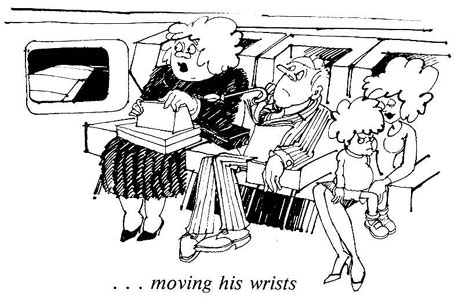

- Cramped between a large nervously twitching elderly lady, with

enormous quantities of hand luggage and a young mother with an ominously

green-coloured child, our hero cannot read the journal that requires

moving his wrists from time to time – if there is a journal available,

of course!

- After attempting for some time to attract the attention of the

stewardess our hero is informed that he can’t have a drink –

“We’re serving lunch and you’ll have to wait."

- A plastic tray, wrapped in plastic film, containing plastic food

is dropped on the plastic shelf which is threatening to amputate our

hero’s kneecaps. His large neighbour, in one of her more alarming

convulsions, tips scalding coffee in our hero’s lap. He hasn’t

eaten anything as he dropped his cutlery while fighting the “easy-open”

pack in which they were sealed. He asked for some more, but has seemingly

achieved invisibility.

- Eventually he manages, after much contortion, to make his seat

recline – tipping coffee on the gentleman seated behind. He dozes

fitfully until he is thrown forward by his seat which the stewardess

has pushed back into the upright position prior to landing.

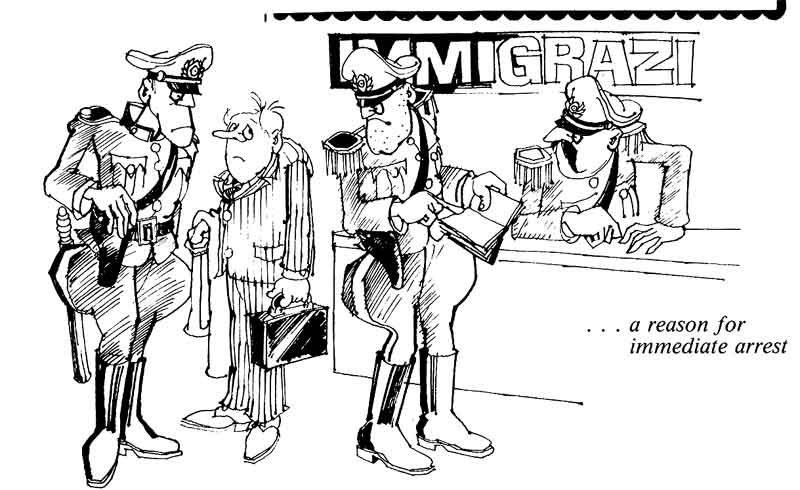

- In the hot, overcrowded arrivals hall, our hero is directed to

several different immigration control desks and eventually, by chance,

arrives at the one reserved for non-nationals where the official examines

every one of the 94 pages in our hero’s passport, seemingly hoping

to find a reason for immediate arrest.

- Our hero’s battered, if not torn suitcase, is the last

to be hurled onto the small mountain of assorted luggage on the floor.

- Nobody greets him, except perhaps a suspicious customs officer,

who threatens to squeeze out all our hero’s toothpaste and dissect

the lining of his suits.

- A half-hour ride in a shared taxi (total six passengers) for

which he waits 45 minutes and our hero arrives at his hotel –

at least, a building called “Hotel Whatever”, but there

is no doorman, just a desk clerk, whose memory needs jogging with a

$10 bill before he will admit that there is a room available. “Sorry

sir, your confirmation slip is incorrect, we are fully booked –

there is a conference/delegation/strike/state visit.”

- The “express” elevator doesn’t work so eight

flights of stairs later our hero enters his room. There is no balcony,

just a view – the back of the hotel next door! His suitcase arrives

30 minutes later. The boy who delivers it seems reluctant to leave and

when tipped assumes an expression that would reduce a lesser mortal

to dust, but not our hero. Into battle!

- Room service? “Sorry sir, not after 8 o’clock, except

tea. That arrives 30 minutes later without sugar or milk, and cold.

- Not beaten, our hero looks forward to his shower, which if of

masochistic leaning he will enjoy, as the alternate scalding and freezing

is quite invigorating.

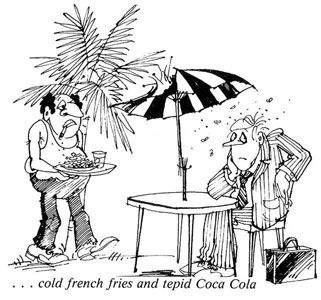

- Now to dinner. Well, almost, the restaurant is closed at 9pm.

Never mind, our hero heads for the 24-hour “coffee shop”

where his palate is delighted by underdone hamburger, cold French fries

and tepid Coca Cola. No ice!

- And so to bed, secure in the knowledge that with luck his agent will be in his office tomorrow (if he remembered our hero’s arrival date) and perhaps a programme of meetings has been proposed. If so, it will either induce a state of nervous exhaustion or near insane frustration in the mind of our intrepid hero – one of the front line soldiers in Britain’s briefcase army in the export war.

However, the final Baker Perkins Annual Report – 1986 – showed further rapid growth in overseas business to £222.4m or nearly 85% of total group sales, £120m being exports from the UK. The Group received six Queen’s Awards for Exports between 1977 and 1991 – two for Biscuit machinery, two for Printing machinery, one for Special Projects and one for Packaging machinery. (See also Queen’s Awards for Industry).

Now see:

Baker Perkins in Africa

Baker Perkins in Asia

Baker Perkins in Australasia

Baker Perkins in Europe

Baker Perkins in Latin

America

Baker Perkins in the

Middle East

Baker Perkins in North

America

Baker Perkins in South East

Asia

The cartoons included above were by Ivan Cumberpatch, a frequent contributor to "Contact". More of his work can be seen in Humour at Work.

To be continued.

All content © the Website Authors unless stated otherwise.